Playing with words: memorable

a) Where have you seen or heard this word used?

b) Use the word "memorable" in a sentence:

c) What do you think "memorable" means?

d) Which parts of the word "memorable"' give you a clue about what it means?

a) Fill in the chart below.

| i) Copy the sentence on page 20 which includes the word "memorable" and also the neighbouring sentence or sentences which help tell you what it means. | ii) What do these sentences tell you that "memorable" means? |

|

|

|

c) Use the word "memorable" in a new sentence:

d) Pause, look and think back. Something I'm still wondering about the word "memorable" is:

This task can be completed with pen and paper.

Equipment

"Playing with Words", pages 20 to 23 of School Journal Part 4, Number 3, 2004

Click here for a copy the written text for this resource, Playing with words.

- Students do tasks a), b), c), and d), then read the text before doing the remaining tasks.

- Tasks a), b), c), and d) tap into students' prior knowledge of the word.

- Task e) assesses student ability to use contextual clues to interpret the meaning of the word.

- Tasks f) and g) will show if, and how, students have modified their original understanding of the meaning of the word.

- Task h) prompts students to check their thinking, and will make their thinking explicit.

- apply their knowledge of word families

- infer ideas and information that are not directly stated in the text

as described in the Literacy Learning Progressions for Reading at: http://www.literacyprogressions.tki.org.nz/The-Structure-of-the-Progressions.

NOTE: There is no single correct interpretation of a text, and it can be interpreted at different levels (more or less 'deeply'). However, some interpretations are simply wrong. Students need to make logical connections between text and their interpretation of its meaning.

This resource was trialled by 68 year 7 and 8 students from three schools.

Word knowledge: moving along a continuum

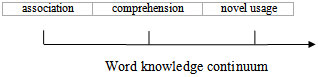

Because an individual word fits into a complicated system of language, there are many things to learn about any particular word and there are many degrees of knowing (Nation, 2001). Therefore, learning a word can be thought of as an incremental process along a continuum of word knowledge. Stahl (1986) suggested three stages of word knowledge: association, comprehension, and generation. At the association level, students can make accurate associations with the word, although they may not understand its meaning; at comprehension level, they can understand the commonly accepted meaning of a word; and at generation level, they can use the word in a novel context. [1] This vocabulary resource enables students to increase their knowledge of a word from whatever point it lies along the knowledge continuum – from association at the first step of vocabulary knowledge, through to comprehension and novel usage.

[1] Kirton, N. (2007). Vocabulary acquisition: a literature review. Wellington, New Zealand: NZCER Press.

From recognising words to building a broad understanding

The word 'memorable' contains clear roots in the word 'memory'. For this reason it is a good word to build understanding upon. Students also reflect on their knowledge of the word and look at the context in the story Playing with Words in which 'memorable' is used to build their understanding of its meaning.

Task a). Students are asked about the first step in vocabulary acquisition, i.e., where they recognise the word from. About a third of students in the trial cited funerals and memorial services as the source for seeing or hearing the word, e.g., At Sir Ed's funeral.

Task c). The definitions students write hereexplicitly show their level of comprehension of the word. Almost all students wrote a short definition of 'memorable' as something or someone that is remembered. A small group defined the word as solely applicable to people who have died. Trials showed that the definition most students used at this point of the resource was extended in the remaining exercises.

Task d). This assesses students' ability to find meaning by identifying rootwordsand word parts. Most students connected 'memorable' to 'memory' and/or 'remember', e.g., It looks like memory, and,'Mem' comes from re'mem'ber. However, only a small group identified the suffix 'able' in 'memorable' as meaning 'capable of', e.g., 'Able' means you can do it. (See the VAT section below for more on suffixes).

At this point, students read the story Playing with Words, in which an image of missiles described as going 'really, really fast' is made more vivid and memorable by the verb 'rocketed'. The application of 'memorable' in the less usual context of writing and intentional effect gives students the opportunity to form a deeper understanding of the word.

Task e) i). This task assesses two skills: firstly, basic word recognition in identifying the word 'memorable' in the story; and secondly, the ability to identify the surrounding text which carries meaning. Most trial students found the word 'memorable' in the story and copied the word in a brief and appropriately meaning-giving context into e) i), i.e., the first paragraph:

"When I was a little boy, I loved playing with words and phrases in my mind. I was always trying to make them more memorable. For instance, if someone said "the missiles went really, really fast over the sky", I'd change that line to something like "the missiles rocketed over the sky".

The first sentence only is also acceptable. About half of the students copied other memorable events from the story as well, such as "I felt such a huge rush of exhilaration that I knew I wanted to spend the rest of my life writing" from page 22. While this and other examples are certainly examples of memorable events, for the sake of simplicity and focus students should be restricted to the one example where the word 'memorable' is used. The extra examples students gave appear to be a result of confusion as to what the task required, including the misunderstanding that the whole table had to be filled. A small group put the text sample in the wrong column.

Task e) ii). Using context is an important part of working out the meaning of a new word. Context is also important in learning to extend knowledge of a word.In e) ii) students are asked to write about the meaning of 'memorable' suggested by the text they chose in e) i). About half of the trial students successfully completed the task by concentrating on what the text suggested about the meaning of 'memorable', e.g., It tells you that making something sound more interesting you will remember it better. The remaining trial students mostly paraphrased the text or commented about the story in general rather than focussing on the meaning of 'memorable', e.g., When he was little he was always trying to make words memorable. Summaries of the narrative generally do not tell us anything new about the meaning of 'memorable'. The difficulty of this task is probably due to the table format and the novel aspect of focussing on word meaning in the context of a story rather than on character or narrative. It is reasonable to predict that more vocabulary work of this kind will reduce task confusion.

Task f) About half of the trial students showed increased word knowledge by writing a broader definition of 'memorable' than they did in c), for example, this trial response to e): Creating something you want to be remembered and a past incident or memory that won't be forgotten, compared to the same trial student's answer for c): A past incident that won't be forgotten.

A small group seized on the use of 'memorable' in Playing with Words and ran with it to the exclusion of all other meaning when they wrote a definition in f), e.g., Playing with words to make them more fun, and, You make the sentence more interesting. These two students answered, ?, and When someone dies you memorable respectively for c). These students show some understanding of the less widely used meaning of 'memorable' in the story despite having little or no prior knowledge of the word's more widely understood meaning. This may indicate that some students with a relatively low vocabulary are actually competent with vocabulary when applied to a task.

Task g) This assesses the students' ability to generate use of the word in a new way (novel usage is considered to be the highest stage of word knowledge). About half of the trial students wrote a more complex and novel sentence than they did in b), for example, this response to g): I want to create an amazing piece of art that would be memorable, compared to the same student's trial response to b): Last Christmas was very memorable. This student has demonstrated a shift along the vocabulary acquisition continuum for this word by drawing on the meaning of 'memorable' explored in Playing with Words. Task h). Students may raise issues or questions about the way their understanding of the word has developed. A small group of students asked questions along the lines of how they could make life more memorable. This might provide a starting point for a class discussion or a way forward.

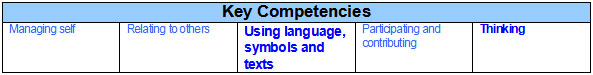

The following section is about what the English team at NZCER call vocabulary acquisition technique (VAT) and is presented as an example of how you might foreground the Key Competencies within reading. In particular, it exemplifies how you might foreground "Using language, symbols, and texts" and, to a lesser extent, "Thinking" within reading through a focus on applying language strategies to find the meaning of new words. VAT teaches students a strategy that will help them become more active interpreters and users of words. This idea is expanded below. In the table directly above, "Using language, symbols, and texts" has the largest bolded font because it is the most important to this particular example. Working with new words

How should students approach new words?

The following text selected from Playing with Words (p 20) provides the opportunity to teach some vocabulary acquisition techniques.

"When I was a little boy, I loved playing with words and phrases in my mind. I was always trying to make them more memorable. For instance, if someone said "the missiles went really, really fast over the sky", I'd change that line to something like "the missiles rocketed over the sky".

Applying vocabulary acquisition technique (VAT)

The word in the text we are looking at is 'memorable'. What does it mean? The most obvious clues here are the parts inside the word, which are clearly recognisable. The word 'memorable' contains most of the word 'memory', so we can be almost certain that 'memorable' has something to do with memory. The other big clue inside the word is the suffix 'able', which means capable of, or worthy of, as in breakable, agreeable, lovable and (slightly different) collectible. And in this case 'memorable' does mean worth remembering. (For interest's sake, the 'mem' inside 'memory' and 'remember' comes from the Latin word memor: mindful.)

We don't often see the word 'memorable' in relation to words and sentences − it usually applies to people and events. What does it mean here? The first clue is when the writer explains how he makes words and phrases more memorable: "I'd change that line to something like "the missiles rocketed over the sky"." The description which the writer has made more memorable with the verb 'rocketed' holds a big clue as to what memorable means here. Look at the difference between the sentence describing the rockets moving "really, really fast over the sky" and the second version saying "the missiles rocketed over the sky". Because lots of things move really fast but only a few things can rocket, the second version creates a more vivid and accurate picture of the missiles in our minds. By comparing these two versions, it appears that the more vivid and energetic sentence is more 'memorable'.

What does the word's 'electrical value' tell us? Is the word 'memorable' positive or negative? By looking at the nearby sentences we can see that the phrase, "I loved playing with words", is positive. But before deciding that memorable is probably a positive thing we should think about the missiles, which are a negative thing. Looking closely, we can see that the writer is not really interested in missiles but in the best way to describe them, so it appears that 'memorable' is probably a positive thing after all. The text has shown us that the word 'memorable' can also apply to words − not just people and events − and that we can make things we say and write more memorable by choosing the right words.

- attachment to neighbouring words and sentences (e.g., compare the memorable sentence to the first one);

- 'electrical value' (whether the word is in a positive, negative, or neutral context);

- word parts, (including suffixes such as able, ible, and ful – as in helpful).

- Blachowicz, C.L.Z., & Fisher, P.J.I., (2006). Teaching vocabulary in all classrooms (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

- Nation, I.S.P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- Kirton, N. (2007). Vocabulary acquisition: a literature review. Wellington, New Zealand: NZCER Press.

- Can you see through it?

- Protecting Our Kaimoana

- An Inspiration

- Sea-dog

- Newspaper report

- Activities keep you on the edge

- Looking at insects

- Octopuses

- Hercules Beetle

- Keiko the killer whale

- Albatross

- Flood prevention

- Transparent, translucent or opaque?

- Voices in the Park

- Interdependence loopy

- Where did the water go?

- Changes of state II

- Playing with words: implode

- Describe what you're experiencing

- Ko Bakong