Readers make connections between what they know and what they read.

Student:"When I make connections I'm thinking about my memories and the book all at once."

Teacher:"Keeping in mind what you've just said about the main idea here, are there comparisons you can think of between this text and the one on global warming?"

- Effective Literacy Practice Y1–4 p. 131

- Effective Literacy Practice Y5–8 p. 142

- Duffy pp. 81–86

- Harvey and Goudvis pp. 67–80

- Miller pp. 53–72

Other resources with a focus on making connections:

- Research and examples of how teachers activate prior knowledge building on their students' familiarity with a topic to develop comprehension.http://www.ncrel.org/sdrs/areas/issues/students/learning/lr100.htm

- Using the think aloud strategy to model making connections.http://www.nwrel.org/learns/tutor/spr2001/part3.html

Readers form and revise hypotheses or expectations about texts.

- Effective Literacy Practice Y1–4 p. 132

- Effective Literacy Practice Y5–8 p. 143

- Duffy pp. 81–86

- Miller pp. 157–171

Resources

Readers use the ideas in texts together with their prior knowledge to create images in their minds.

- Effective Literacy Practice Y1–4 p. 133

- Effective Literacy Practice Y5–8 p. 145

- Duffy pp. 95–101

- Harvey and Goudvis pp. 97–105

- Miller pp. 73–92

- 'Mind Pictures: Strategies That Enhance Mental Imagery While Reading':http://www.readwritethink.org/lessons/lesson_view.asp?id=792http://www.educationworld.com/a_curr/profdev/profdev094.shtml

- Visualisation transforms students from passive to active readers, while improving their reading comprehension.

Resources

- Rock Cartoon

- Learning to Read

- Sand dunes

- Born to be wild

- Describing logos

- The Rice Balls

- To work or not

- Skaters – are they really to blame?

- What is the main idea?

- El Flamo

- The Forgotten fork I

- Giant weta

- Close Encounters I

- Close Encounters II

- Pest Fish

- Feathery Friends

- The Weevil's Last Stand

- Big Shift

- No Big Deal

- The Sleeper Wakes

- Finding a fine mat

- A very special frog

- Great-grandpa

- Ecological islands

- The Terotero

- A gift for Aunty Ngā

- Don't miss the bus!

- It's snowing - again!

- Once bitten

- The impossible bridge

- Saying goodbye

- Why do I blush?

- Flood

- Rock doc II

- Giant Weta II

- Breakfast for peacocks

- White Sunday in Samoa

- Tom's Tryathlon

- Motocross

- Daisy Data

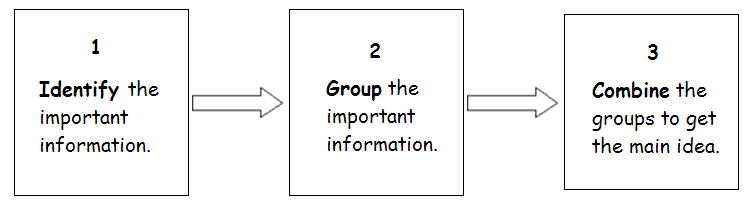

What is the main idea?

- Effective Literacy Practice Y1–4 p. 133

- Effective Literacy Practice Y5–8 p. 148

- Duffy pp. 117–124

- Harvey and Goudvis pp. 122–143

- Miller pp. 141–156

Resources

- The Whispering Giant

- The Winner Loses

- Creating sculptures

- Flying to remote places

- The Moa

- George and Lennie

- The Diving Competition

- The Dinosaur climber's kit

- No Circulars

- Marathon - The Legend and the Truth

- Haircut lament

- Mouse party

- The magic wand

- Reading pictures

- Making chapattis

- Buttercup

- Huckleberry Finn

- Delicious Steamed Kai

- Spider

- Bug the Aphids

- Socrates

- Learning to Read

- Hide-and-go-seek

- Sand dunes

- Sea-dog

- Parcel

- Black Holes

- Let's make a bird ball II

- Night in the forest

- House Bus

- What is it? II

- Brushes and hedgehogs

- Prescription

- Song of the Vagabond Tomato

- Selecting the Trees

- Theft costs us all

- A story about Māui

- The Lion and the Monkeys

- Newspaper report

- Porridge

- Magic stuff

- Activities keep you on the edge

- A Shattering Breakthrough

- The Bat

- Why possums live in trees

- Mako shark

- Moods

- The windy night

- Sofi's first night away

- Down Comes A Tree

- Where angels fear to tread

- Fā'aluma

- Steep streets

- Wearable Art show

- Runaway weather balloon

- Do you get it?

- A Load of Junk

- Pig Hunt

- Hedgehog

- The Foolish Man

- Diving

- Happy birthday consumer

- Shark Scare

- Fever

- Flea feast

- Personal Mail

- Grey hair

- Be my Valentine

- Mmmm... mine

- Saving our national bird

- To work or not

- Skaters – are they really to blame?

- Parachuting

- What is the main idea?

- The gift

- If I were...

- What or who are they?

- What is Susan making?

- What or who am I?

- Rock Doc

- Taniwha

- The Kuia and the Spider

- Giant weta

- Fat, four-eyed and useless

- What is this tiny thing?

- Memory

- What is it?

- Tangiwai

- Cuthbert's Babies

- Voices in the Park

- What could it be?

- Boy's Song

- Feathery Friends

- No Big Deal

- The Sleeper Wakes

- Great-grandpa

- Ecological islands

- The Terotero

- A gift for Aunty Ngā

- It's snowing - again!

- Once bitten

- The impossible bridge

- Up from the Ashes: "grateful"

- Playing with words: memorable

- Playing with words: implode

- White Sunday in Samoa

- Tom's Tryathlon

- What are "they"?

- Daisy Data

- Railway Crossings

- Too Much Noise!

- Whale watch

- Which one am I? (1)

- Which animal am I?

- Which one am I? (2)

- Fat, four-eyed and useless II

Readers use text content as well as background knowledge to come to conclusions that are not stated explicitly in the text.

- Effective Literacy Practice Y1–4 p. 132

- Effective Literacy Practice Y5–8 p. 146

- Duffy pp. 102–108

- Harvey and Goudvis pp. 105–116

- Miller pp. 105–121

Readers briefly retell a part, or a whole text.

- Effective Literacy Practice Y1–4 p. 133

- Effective Literacy Practice Y5–8 p. 149

- Duffy pp. 125–132

Resources

- Working from home

- Grey hair

- The Rice Balls

- Memory

- Voices in the Park

- To Spray or Not to Spray?

- Close Encounters I

- Close Encounters II

- Pest Fish

- The Weevil's Last Stand

- Big Shift

- No Big Deal

- Finding a fine mat

- A very special frog

- Great-grandpa

- A gift for Aunty Ngā

- Don't miss the bus!

- Saying goodbye

- Why do I blush?

- Flood

- Rock doc II

- Giant Weta II

- On the Reclaim

- Get out of my hair!

- Kissing Frogs

- 'Apa!

- Wolf

- The Blink-off

- And the Winner Is...!

- Unfair!

- My Dad, the Soccer Star

- Sports Day

- Kebabs

- Breakfast for peacocks

- Motocross

- Daisy Data

- No More Cats

- Katie's Birthday

Readers make judgments about what the author is saying.

- Effective Literacy Practice Y1–4 p. 134

- Effective Literacy Practice Y5–8 p. 151

- Duffy pp. 141–151

Resources

- Washday for the clouds

- The night the lights went out

- Making comparisons II

- Making comparisons

- Paikea

- El Flamo

- The Forgotten fork I

- What or who am I?

- Taniwha

- Taniwha messages

- The Kuia and the Spider

- Fat, four-eyed and useless

- Tangiwai

- Cuthbert's Babies

- Voices in the Park

- What could it be?

- The Sleeper Wakes

- Great-grandpa

- Dancing Cossacks

- Hugo

- White Sunday in Samoa

- Fat, four-eyed and useless II

- Effective Literacy Practice Y1–4 p. 133

- Effective Literacy Practice Y5–8 p. 150

- Duffy pp. 149–155

- Harvey and Goudvis pp. 143–167

- Miller pp. 157–171

- Effective Literacy Practice Y1–4 p. 132

- Effective Literacy Practice Y5–8 p. 144

- Duffy pp. 87–94

- Harvey and Goudvis pp. 81–94

- Miller pp. 123–140

- Clarke, Shirley (2001). Unlocking Formative Assessment, pp. 104–109, Hodder Moa Beckett.

- Walker, Barbara, J (2005). Thinking aloud: Struggling readers often require more than a model, pp. 688–692, The Reading Teacher, Vol. 58, No. 7, April 2005.

- Fordham, Nancy, W (2006). Crafting questions that address comprehension strategies in content reading, pp. 390–396, Journal of Adolescent Literacy, 49:5, February 2006.